|

| St. Thomas, the Angelic Doctor. |

Today marks the feast of St Thomas Aquinas, Dominican friar and Doctor of the Church. Born in 1225, St Thomas joined the Order of Preachers at around nineteen or twenty years of age. After a remarkable career of teaching, preaching and indeed writing, St. Thomas died in 1274, asking in death only that he be granted Jesus Himself. Pope Pius XI advised Christians seeking wisdom to “Go to Thomas.” Was this good advice? To find out we shall consider the Angelic Doctor’s thought on a topic that affects every one every day of their life on earth: sin.

Sin is an ever present reality; it is something we just can’t seem to escape. Even the blessed apostle Paul suffered from the thorn of sin. He did the things he hated and did not the things he loved (Romans 7:15). We, like St Paul, often fall short, we fall into situations which stir up in us conflict, by instinct we call this sin, but what exactly is it?

St Thomas identifies sin as an act, willed by a human being, which is contrary to the eternal law. More simply, it could be said a sin occurs when a person chooses, instead of God, some lower good. Sin is what happens when we forget about God, or in the most grievous cases, when we chose to act against Him. Since it is seemingly ever before us, how then, are we to deal with it?

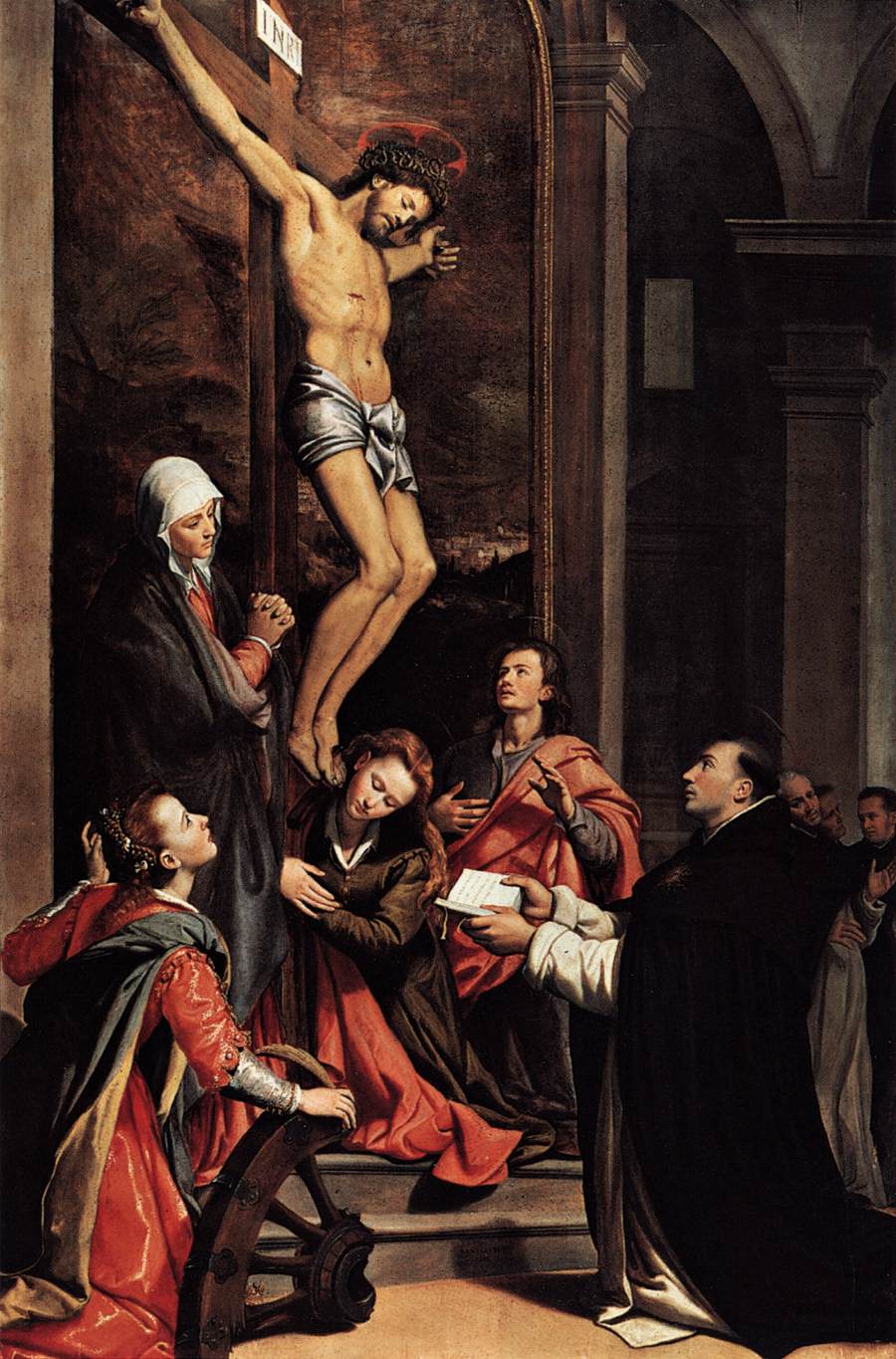

Well, in fact, it is not man who deals with sin, it is God. As Jesus said, He came ‘to give His life as a ransom for many’ (Matt. 20:28). This redemption was achieved on the Cross. Man had isolated himself from God, and was incapable of healing that wound. It was for this reason that the Son became incarnate, by becoming man He could offer to the Father an infinite act of love, which would always be more pleasing to the Father than any sin. St. Thomas demonstrates that Jesus’s sacrifice on the Cross was an act that not only atoned for all man’s failings, but merited for each man salvation. ‘Grace was bestowed upon Christ… the Head of the Church that it might overflow into His members’ (IIIa, q.48 a.1).

The forgiveness of sins comes from Christ’s passion and death, though we continually stumble and even fall, we never lose hope in the infinite merits of our Redeemer, who nailed our sins to his Cross. However, St. Thomas would not want Christian reflection to stop there. The Cross is not only in our past, it is our hope for the future. Thomas remarks that Jesus did not only merit for man salvation, He also offered the perfect example of what it means to be truly human. Sin, Thomas says, is contrary to human nature because it isolates us from our creator, and to know Him and love Him, and to dwell in His love is our purpose. Christ manifested the meaning of our lives through His constant obedience to the Father.

Jesus’s action was our instruction, as the Dominican scholar Torrell puts it. Thus, when we read the words ‘take up your Cross and follow me’ (Matt. 16: 24) we realise this is a genuine invitation. It is an offer, to let our lives be Christianized so that from our flesh might be driven the thorn of sin.

In this context, the value of the sacraments Christ instituted for His Church becomes all the more apparent. When we sin, we turn to God and ask for His forgiveness in the confessional. It is our own Gethsemane moment, a chance to reflect on our sins, and the sins of all, and walk the way of the Cross, the path of humble obedience. Echoing our Lord we have the privilege to say ‘not my will, but yours be done’ (Luke 22:42).

This, I think, would be St. Thomas’s advice for the sinner. Do not fear. For God has sent to us the Redeemer. Let us neither despair of our sins nor boast of our virtues. Rather, let our glory be the Cross. When we can say that, as the apostles did, then we can follow Christ wherever He may lead us. Of course, it isn’t always easy, but that is why we have the Church and her sacraments, and that is above all why Our Lord has made present every day in every part of the world that saving sacrifice, whereby we are fed with His Body and Blood. Salvation has been given us and the bed of Faith made fertile so that grace might abound, all we need do is keep our trust in God and beseech the merits of the Passion.

St. Thomas said all theology was found in the Psalms, well, in times of adversity and doubt we can sing with the psalmist: ‘hope in the Lord, I will praise him still’ and that is the answer to sin.