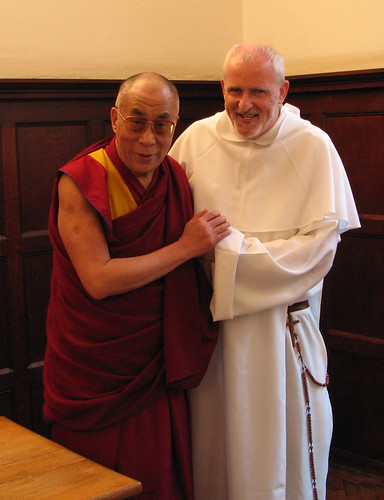

Having already hosted Cardinal Walter Kasper this term, Blackfriars received another distinguished visitor in the person of the Dalai Lama who came to take part in a colloquium on 'Christian and Buddhist Contemplative Prayer'.

The proceedings were opened by Fr Paul Murray, an Irish Dominican who lectures at the Angelicum in Rome. He spoke about contemplative prayer in the Dominican tradition, drawing in particular on the writings of three of the Order's great spiritual teachers, John Tauler, Catherine of Siena and Meister Eckhart. The difficulties of the 14th century, in which these three lived, reflect our own difficulties in many ways, he said, and their experience of and teaching about contemplative prayer can lead us also to compassion and service.

Fr Eugene McCaffrey, an Irish Carmelite from Tabor Retreat House in Preston, spoke about contemplative prayer in the Carmelite tradition. He spoke particularly about St John of the Cross, and of the 'dark nights' that accompany the experience of prayer, times when the one who prays feels that they have lost everything, including, and especially, God. These experiences enabled John of the Cross to write the most beautiful of all spiritual poetry in which the soul's loss is made good beyond her expectations in her union with, and even transformation into, the beloved (amada en el amado trasformada): then everything becomes hers, even God.

The Dalai Lama spoke about his involvement in conversations with Christians, in the first place with Thomas Merton who spent three days with him at Dharamsala. He remembers the great boots Merton was wearing and also their discussion about the Buddhist belief in endless life compared with the Christian belief in one life alone. 'Only this life, created by God', His Holiness quoted Merton as saying, and repeated it ... 'only this life, created by God'. Which implies, he continued, an extraordinary intimacy between God and the one who is thus created. It seems as if Merton thus succeeded in communicating one of the central teachings of Christianity to the Dalai Lama and that he has pondered it ever since.

In speaking about Buddhist contemplation His Holiness said that he could agree with all that had been said by the Christian speakers if the term 'God' were substituted with the phrase 'ultimate reality'. Buddhism also recognises three stages in seeking understanding and wisdom, the stage of knowledge when one learns about things from teachers, the stage of critical enquiry when one engages in study and reflection, and the stage of meditation or contemplation when one seeks to understand reality and illusion. In both Buddhism and Christianity there is the emphasis on compassion and on the fact that contemplative prayer must issue in service of others and a concern for peace.

There was then some discussion about various aspects of Buddhism and links with Christian traditions of prayer. The most fascinating question was whether the reality that is sought in prayer, whether it is called 'ultimate reality' or 'God', is a reality that seeks us.

It was a wonderful moment for Blackfriars. The Dalai Lama had joined the community for midday prayer before the colloquium: his prayerful reverence towards the altar, the tabernacle, and the brethren, was very deeply moving. He spoke as powerfully in the way he was present with us and to us as he did by his words.