Br Romero Radix OP is currently doing a summer placement in a London hospital under the direction of Fr Peter Harries OP. This is the reflection Br Romero has written for this week's edition of St Dominic's Newsletter, the weekly newsletter of St Dominic's Priory, London

Br Romero Radix OP is currently doing a summer placement in a London hospital under the direction of Fr Peter Harries OP. This is the reflection Br Romero has written for this week's edition of St Dominic's Newsletter, the weekly newsletter of St Dominic's Priory, LondonThe king’s leading men wanted to put Jeremiah to death on account of the word of God he had spoken. The king was Zedekiah. The people of Jerusalem were under serious threat of being taken captive to Babylon. Jeremiah had told the king God’s words were these: ‘you shall be delivered into the hand of the king of Babylon.’ Furthermore, if any one should remain in the city he would die by the sword or famine or pestilence, but those that go forth to the Chaldeans – that is the Babylonians - shall live.

The king’s leading men did not like this. They said that Jeremiah’s words were disheartening the remaining soldiers in the city. This is the heart of the matter. What God had in mind and what they had in mind were two different things. What they wanted was in conflict with what God had planned. They did not like God’s plan. They were not willing to accept it. They were not willing to change.

Now, of what relevance is this text to us, today? Well, with the advent of Christ the ministry of the prophet was not abolished. Paul tells us that ‘some He made prophets, some evangelists, some teachers, and some apostles – for the building up of the saints’. So, if we as the body of Christ are to be built up, we have a duty and a responsibility to find out the prophets’ words for our time and to receive them with open hands. To do this, first we must ask ourselves who are the prophets of our time? What are the issues with which they concern themselves? And, what has been our response to their words? These questions are worth serious consideration on our part. It frequently resurfaces in my consciousness that we belong to a community that spans the entire globe. This being the case, we have a great responsibility to remain constantly aware of the issues that are affecting our brothers and sisters around the world – to keep praying for them sincerely and fervently.

So, there is the office of the prophet, but people we live with and work with can also be prophetic. God’s word can be brought to us by many different messengers as a wife to a husband or a child to a parent. What is our response when they tell us something that we do not want to hear, or something that we are not pleased with? Do we sometimes dismiss them outright?

Jeremiah teaches us that God's words are not always what we would want to hear, or what will please us. This being the case, whenever somebody tells us something we do not like, we must always be open to the possibility that it might be the truth. If we never leave a space for this possibility we are operating from pride. This may result in serious division in a home or a work place, and derail us from walking according to God’s will for us.

It is true that Jesus in the gospel from Luke today says that he did not come to bring peace on earth, but, rather division. He says, ‘for from now on a household of five will be divided: three against two and two against three; the father divided against the son, son against father, mother against daughter, and daughter against mother …’

These sayings are striking, but to say that they are inevitable in every family would be to limit the power of love. Granted, divisions might arise, but as Paul says, in every way and as much as is possible try to live at peace with everyone. If indeed we are trying our utmost, then we will always be open to whatever, however displeasing, someone has to say. In this way, we keep ourselves open always to God.

Interestingly, sometimes what we think is displeasing and negative and disheartening is not. Jeremiah was bringing the king’s leading men good news, for he was giving them a word by which their lives would be preserved. But, they could not receive his words because all they had in mind were their ideas. With Jeremiah to learn from we can avoid this mistake.

God bless you

Romero Radix o.p

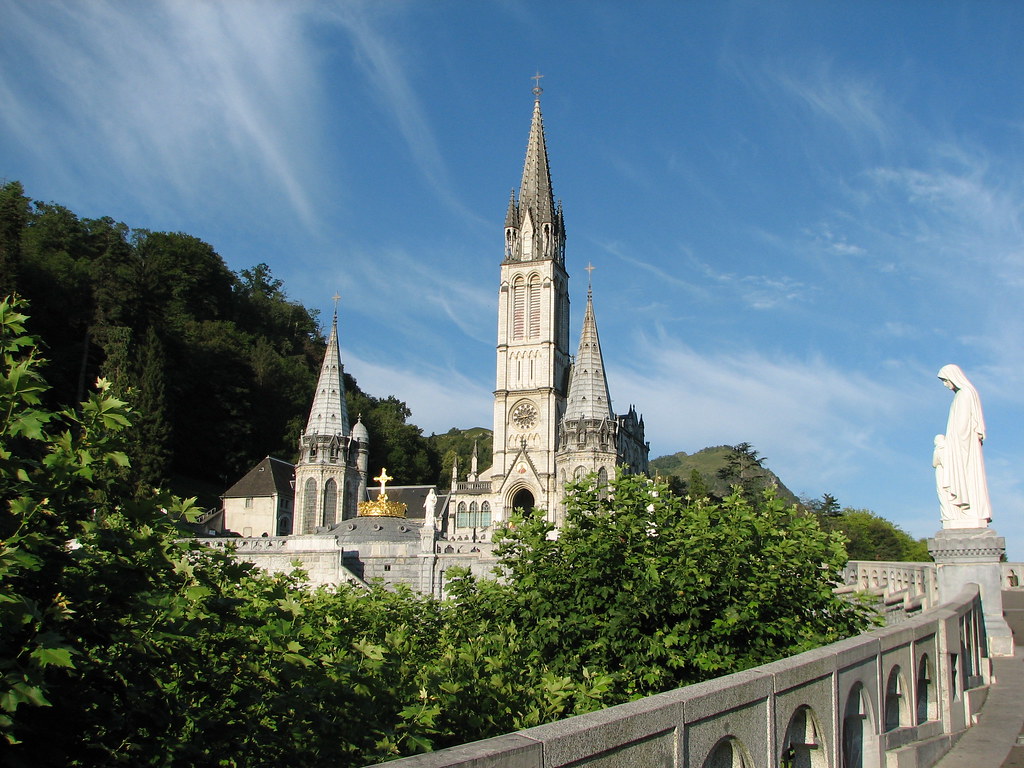

Lourdes was originally a small unremarkable market town lying in the foothills of the Pyrenees. In 1858, Our Lady appeared eighteen times to a fourteen-year-old Bernadette Soubirous. Since the first apparition on 11 February, crowds have come to Lourdes and to the Grotto of Massabielle to fulfill the requests of Our Lady and in search of healing. We came to do the same.

Lourdes was originally a small unremarkable market town lying in the foothills of the Pyrenees. In 1858, Our Lady appeared eighteen times to a fourteen-year-old Bernadette Soubirous. Since the first apparition on 11 February, crowds have come to Lourdes and to the Grotto of Massabielle to fulfill the requests of Our Lady and in search of healing. We came to do the same.

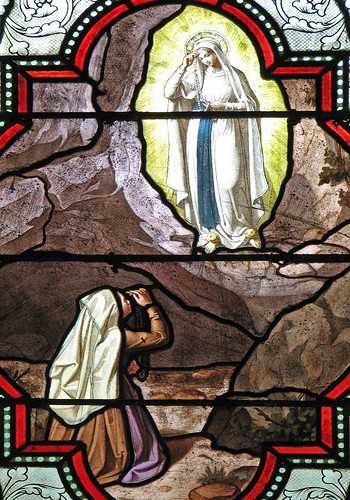

During the 9th apparition, on Thursday 25 February, Our Lady said to Bernadette, "… go drink at the spring and wash there… ". Some pilgrims chose to wash in the baths in Lourdes, others to drink and wash from the taps near the Grotto. Both the baths and the taps are fed by the spring which Our Lady indicated to St Bernadette.

During the 9th apparition, on Thursday 25 February, Our Lady said to Bernadette, "… go drink at the spring and wash there… ". Some pilgrims chose to wash in the baths in Lourdes, others to drink and wash from the taps near the Grotto. Both the baths and the taps are fed by the spring which Our Lady indicated to St Bernadette.

During the 13th apparition, on 2 March, Our Lady said, "Go and tell the priests that people should come here in procession…". It is from this request that the two processions of Lourdes were born. We led the Marian Procession on one evening, during which eight friars carried the statue of Our Lady as we prayed the Rosary. On another afternoon, we walked in the Eucharistic Procession.

During the 13th apparition, on 2 March, Our Lady said, "Go and tell the priests that people should come here in procession…". It is from this request that the two processions of Lourdes were born. We led the Marian Procession on one evening, during which eight friars carried the statue of Our Lady as we prayed the Rosary. On another afternoon, we walked in the Eucharistic Procession.

To be continued...

To be continued...